Read the booklet ‘Imaging famine’.

Do some research across printed and online media and find examples that either illustrate or challenge the issues highlighted in the document. Add your findings to your learning log.

Imaging Famine is a research project and blog that addresses the way famine has been represented in the media, from the 19th century to the present day, and, aims to provoke debate about the political effect of these images.

Notes from the article ‘Imaging Famine’ we are directed to can be found here:

Three articles by David Campbell on his blog make interesting further reading and develop the thoughts in the ‘Imaging Famine’ piece:

- Stereotypes that move: the iconography of the famine

- Thinking images v.20: Famine iconography as a sign of failure

- Imaging famine: how critique can help

Campbell addresses the concerns and contradictions that are fraught in the depiction of famine:

- Famine is often preceded by advance warning of food shortages, but only becomes ‘newsworthy’ once it is happening – the reporting of starving by the media is often the key change that breaks indifference.

- While it is possible to criticise famine photography as “simplistic, reductionist, colonial and even racist” (Campbell, 2010), the production of ‘positive’ images could equally fall into the same trap: The challenge for photography is to find a way of showing the complex political context of famine in a timely way, “before malnourished bodies can be appropriated by the lens.” An example is the 2011 food crisis in the Horn of Africa which only gained focus from the media when the complex, combining factors of drought, conflict, high food and fuel prices, and, funding shortfalls were simplified into the story ‘the worst drought in sixty years’.

- Famine iconography has an effect on Africa which homogenises, anthropomorphises, infantilises and impoverishes, giving a stereotype of a “desperate, poor, passive victim.” (Campbell, 2011a)

- Photography has historically been unable to capture complex political circumstances and the depiction of distress and starvation is a direct representation of the inability of the picture to show cause and context.

- In a Guardian article, art critic Johnathan Jones (2011) argues that critiques of the ethics of the photograph are pointless in relation to famine: “Consciences are awakened by the camera.” Campbell (2011b) believes this simple “either/or proposition of seeing or not seeing” misses the point, as the real question is how can we see more effectively?

- “Famine is made real through a particular visual tradition, and we continue to see it.” (Campbell, 2011b) This thought is illustrated by a 2003 cover from the New York Times magazine which features 36 portraits of malnourished children from a 50 year period and clearly demonstrates that there is a dominant and continuing way of representing this sort of disaster. While it can be argued that these images are necessary as they show what is “going on”, Campbell proposes that this is not the case – they are stereotypes that only show the final stages of famine, more importantly, their continual reproduction serves to obscure the real issues.

The case of ‘Dreaming Food’ by Alessio Mamo

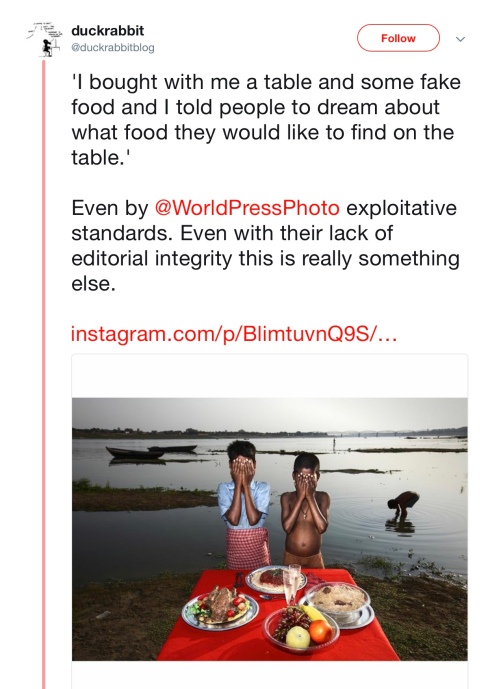

In July I became aware via Duckrabbit of a heated debate that emerged following the photo series ‘Dreaming Food’ by Alessio Mamo on the World Press Photo Instagram account.

Mamo won second prize in the 2018 World Press Photo prize which is the reason he was invited to curate their Instagram account. For part of this he chose to show his 2011 independently initiated project ‘Dreaming Food’, a “conceptual project” in which he shows villagers from Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh in India standing in front of tables laden with fake food. In a statement published soon after the controversy erupted, Mamo explains the project developed from his desire to highlight western food waste, particularly at times like Christmas, by contrasting a typically luxurious western table of food in a poor context. He is at pains to describe a collaborative process where he asked for volunteers to contribute to the project and that the people in the images were not suffering from malnutrition. He feels he was respectful of the people photographed and worked with them in an honest way and that the aim of the project was to make Western people think in a provocative way about the issue of food waste.

The main criticisms of ‘Dreaming Food’ are that the images are “unethical, staged and poverty porn” (Beaumont, 2018) and looking through the comments following the tweet from Duckrabbit there is a large amount of anger and vitriol cast towards both photographer and World Press Photo.

There is a distinction that is made by some that the work is unethical as photojournalism yet fine if viewed as conceptual art, although often downgraded to the less critical ‘crass’. I do not share this distinction – the work is unacceptable through whichever prism it is viewed. The explanation and apology from Mamo appears to be heartfelt however, and I feel sorry for the backlash he has received – I wonder what advice and feedback he had about this series? I assume nothing to the extent he faced here given it originates from 2011. Antonio Olmos, himself a World Press Photo winner, eloquently sums up the problems with the project:

“The trouble with photojournalism is that we are expected to be journalists and artists at the same time and that is a fine line to traverse without getting it wrong. The problem is that the photos first appeared on the World Press Photo Instagram – an organisation that is supposed to promote journalism. The set clearly states it’s a conceptual project and this shouldn’t be on it. The second issue is that it shows plastic food set in front of what I am supposed to believe are hungry people. That is cruel and shallow and demeaning.” (Beaumont, 2018)

Olmos points to a seemingly similar project ‘What the world eats’ by Peter Menzel which features portraits of families from 24 countries around the world alongside the food they buy weekly and its cost. For Olmos, this shows the gap in diets and what can be afforded as well as the wide variety of cuisine and palates. Looking at the two series’ side by side the most obvious difference is that the people in environmental portraits of Menzel’s series appear relaxed and part of the process, they are also photographed in the same way despite being from very different parts of the world which suggests a democratic viewpoint. The aesthetic choice Mamo makes in his series emphasise the colour saturation through the use of flash and his sitters, rather than appearing relaxed, are directed to hold their hands over their eyes in front of the table set up with food.

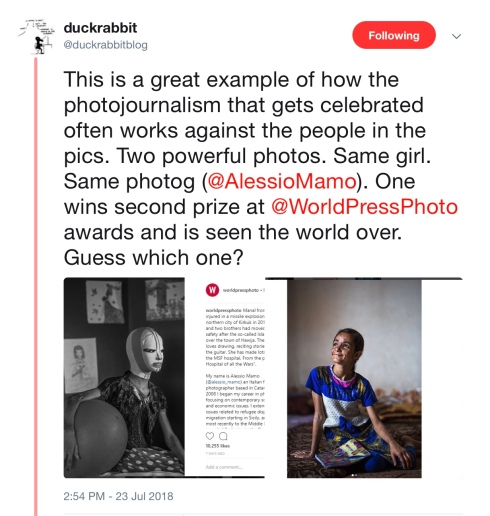

A final aside to Mamo’s work comes again from Duckrabbit and this tweet:

The two pictures shown are of the same girl, and the black and white image is the one that won Mamo second prize in the World Press Photo awards. Duckrabbit makes the point that both images are powerful and praises Mamo for taking the second, colour image, yet, it is the first that wins the award:

“Once we start to explore why one of these photos is award winning and the other is not we have to have some difficult conversations. The use of black and white. The blank canvas. And most of all our superiority. The othering

…

The smiling girl could be my daughter. The masked girl is an alien.”

These powerful words resonate with me and cause me to ask many questions about the power of photography and specifically, whether the single image is a valid way to explore any sort of narrative storytelling. Importantly, the point here is not a criticism of the photographers work but of the media (and organisations like World Press Photo) who are the gatekeepers – instinctively I think it is the second image of this pair that Mamo would prefer to publish, but, understanding the conventions of competitions like the World Press Photo Award mean he also has to make the first image.

Bibliography:

Beaumont, P. (2018) Row erupts over ‘poverty porn’ images of Indian villagers with fake food. The Guardian, 24th July 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jul/24/row-erupts-images-indian-villagers-fake-food-alessio-mamo?CMP=share_btn_tw [accessed 23rd September 2018

Campbell, D. et al (2005) Imaging famine. Available at: https://www.oca-student.com/resource-type/imagingfamine [accessed 6th June 2018]

Campbell, D. (2010) Stereotypes that move: The iconography of famine. David Campbell Blog, 20th October 2010. Available at: https://www.david-campbell.org/2010/10/20/stereotypes-that-move/ [accessed 23rd September 2018]

Campbell, D. (2011a) Thinking images v.20: Famine iconography as a sign of failure. David Campbell Blog, 16th July 2011. Available at: https://www.david-campbell.org/2011/07/16/thinking-images-v-20-famine-iconography-failure/ [accessed 16th July 2018]

Campbell, D. (2011b) Imaging famine: how critique can help. David Campbell Blog, 19th August 2011. Available at: https://www.david-campbell.org/2011/08/19/imaging-famine-how-critique-can-help/ [accessed 16th September 2018]

Jones, J. (2011) Consciences awakened by the camera. The Guardian, 22nd July 2011. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jul/22/consciences-awakened-camera [accessed 16th September 2011]

Murabayashi, A. (2018) Alessio Mamo’s photos are abhorrent, and so is World Press Photo’s response. Photoshelter Blog, 23rd July 2018. Available at: https://blog.photoshelter.com/2018/07/alessio-mamos-photos-are-abhorrent-and-so-is-world-press-photos-response/ [accessed 23rd September 2018]

Thomas, M. (2018) Is it ok to exploit poor Indians in the name of photojournalism? Quartz India, July 24th 2018. Available at: https://qz.com/india/1334792/world-press-photo-controversy-over-alessio-mamos-images-of-indians/ [accessed 23rd September 2018]