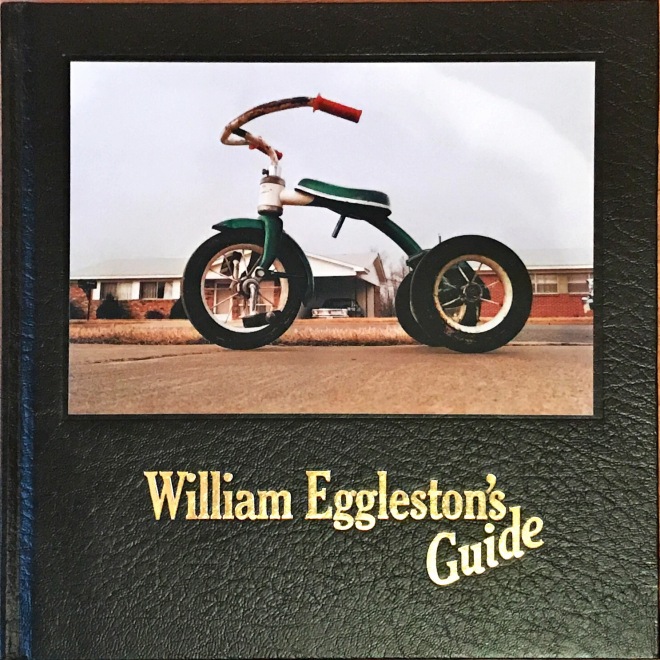

The 1976 New York MoMA exhibition ‘Color Photographs by William Eggleston’ marked a paradigm shift in the acceptance of photography as art and of colour, rather than black and white, as a serious and valid form of photographic expression while also shifting ideas about the nature of photography away from social document to the personal vision. The catalogue of the show, ‘William Eggleston’s Guide’, was the first photographic publication printed in colour by MoMA and continues to be influential, as well as being noted as a landmark in the acceptance of photography as an art form.

At the time of the exhibition Eggleston was little known. MoMA curator John Szarkowski selected 75 images from the 375 brought to him by Eggleston for the exhibition (48 appeared in the Guide) which raises an interesting question about the significance of the editor/curator in the process of making a body of work. Eggleston famously only takes one image of each subject he photographs, a process he describes as ‘photographing democratically’. In ‘The Colourful World of Mr. Eggleston’ (2009) he argues, in typically enigmatic fashion, that this “personal discipline” is necessary because taking more than one picture of one thing would lead to confusion when trying to select the best shot. This inability, or unwillingness, to edit makes the contribution of Szarkowski significant in distilling the images he was presented with into a coherent body of work.

Szarkowski’s introduction to William Eggleston’s Guide

In the introduction to the ‘Guide’, Szarkowski makes an impassioned argument about the validity of colour in photography, the nature of photography itself and why the work of Eggleston is an important change from what has gone before.

“Whatever else a photograph may be about, it is inevitably about photography, the container and the vehicle for all its meanings.”

Szarkowski describes photography as a “system of visual editing”, that is, when taking a photograph, the photographer has to choose from an infinite number of possibilities while also needing to be in the right place at the right time. Despite the world containing “more photographs than bricks” Szarkowski argues that they are also all different, even conscious duplication (for example an earlier work by a master) is impossible to duplicate exactly. Although a random approach to photography will create unique frames, these are likely to be only marginally interesting: it is the photographer that adds intelligence to the mindless mechanisation of the camera through “tradition and intuition – knowledge and ego”. The richness of subjects available to the photographer explain the common trait of prowling, an act through which they ignore “many potentially interesting records while they look for something else.”

Colour: the enormous complication

Photography came of age as a medium with compositional strengths and values in the early part of the twentieth, for example through “exceptional” talents like Stieglitz and Atget who learned to use “the entire plate with consistent boldness” resulting in a new system of indication, based on the expressive possibilities of the detail. This “new pictorial vocabulary” of photography that had achieved set conventions on how to describe the world in meaningful ways, was thrown into chaos with the introduction of colour film. More did not mean better and colour represented a problem that the educated intuitions of the serious photographer chose not to embrace.

Although colour photography was made this was mainly commercial. In an art context, at best colour work was interesting but they were often little more than “black-and-white photographs made with color film” in which the colour was either extraneous or focused on colour relationships rather than subject matter. Szarkowski singles out the studio work of Irving Penn and Marie Cosindas as rare successes in colour photography. Outside the studio however, it has been “either formless or pretty” with the meaning of colour being ignored.

New colour photography

Szarkowski notes an increased confidence and more ambitious spirit in the use of colour in photography during the 1970s with pictures that are not just photographs of colour, or even shapes, textures, objects or events but photographs of experience. Photographers such as Eliot Porter, Helen Levitt, Joel Meyerowitz and Stephen Shore are cited as photographers who worked as though the world existed in colour rather than as a separate problem served in isolation. The resemblance between this work and the vernacular pictures of “the ubiquitous amateur next door” is challenged by asserting that the “difference between the two is a matter of intelligence, imagination, intensity, precision, and coherence.”

Eggleston’s subjects

Szarkowski describes Eggleston’s work as “consistently local and private”, on the surface “as hermetic as a family album.” If the subjects are thought of as trivial then this is in keeping with earlier photographic work that is taken in the real world. The difference Eggleston presents however is that rather than producing social documents his photographs are private and esoteric, like a diary: “we see uncompromisingly private experience described in a manner that is restrained, austere, and public, a style not inappropriate for photographs that might be introduced as evidence in court.”

Eggleston’s photographs would lose all meaning in black and white as they are unconcerned with large social or cultural concerns, seemingly concerned only with describing life: “real photographs, bits lifted from the visceral world with such tact and cunning that they seem true, seen in color from corner to corner.”

The pictures are of interest because they contradict expectations of bland, synthetic American life. They are: “patterns of random facts in the service of one imagination – not of the real world” as pictures they are “perfect: irreducible surrogates for the experience they pretend to record, visual analogues for the

quality of one life, collectively a paradigm of a private view, a view one would have thought ineffable, described here with clarity, fullness, and elegance.”

Criticism of ‘Photographs by William Eggleston’

O’Hagan (2017) notes that the reviews if Eggleston’s 1976 MoMA exhibition were savage with the work dubbed banal and boring, “cracker chic” and “the most hated show if the year.” Dickinson (2016) states that it was the combination of Eggleston’s snapshot scenes of seemingly blandly nondescript Southern life combined with the use of colour, regarded as “vulgar, garish and trashy”, that so incensed the critics. The Village Voice stated in accusatory terms that “some sort of con had been worked” and The New York Times described the show as “a case, if not of the blind leading the blind, at least the banal leading the banal.” Hilton Kramer, the art critic of the New York Times responded scathingly to Szarkowski’s description of Eggleston’s style as “perfect” with: “Perfect? Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly.” (Badger, 2001: 143)

Eggleston’s use of colour

In ‘The Colorful Mr. Eggleston’ (2009), Martin Parr describes Eggleston as using “nothingness colour” in his pictures, that is the colour of everyday life – not decorative, just ordinary. The reason the pictures are so radical is because they are so underplayed. Geoff Dyer sees Eggleston’s aesthetic as a continuation of the existentialism that Robert Frank displayed in ‘The Americans’. Rather than black and white being central to this philosophy, Eggleston’s use of colour adds a complicated variable into the mix: “What in black-and-white looked like a nothing picture could in colour become something extraordinary.” Eggleston’s revolutionary use of colour was not to seek out subjects because of this, but, to photograph them because the world was in colour: “If Eggleston photographs an orange…it is because the orange is part of the world…Effectively, the whole world is an orange…Once Eggleston had really ‘learned to see in colour’, the orange lost its special status. It became just another fruit.” (Dyer, 2005: 249)

The dye sublimation process

Eggleston’s snapshot aesthetic and approach to composition is said to have been influenced by his hobby as a young man of watching amateur snapshots being developed at the local drugstore where his friend worked. When he began to print his own photographs however, the printing choice was much more sophisticated, and expensive. At the time, the dye sublimation process he chose was only used in fashion and advertising, the complicated printing technique was tedious and the most expensive technique Eggleston could have chosen at the time with each print costing several hundred dollars to produce. The process required multiple steps and four separate printing plates, one for each of the primary colours and one for black. Each print took a minimum of three days to produce but resulted in deep saturation, Eggleston noted being stunned by the quality of the prints when he first has some made. (Cocker and Holzemer, 2009) Although Eggleston’s compositions resembled snapshots, the use of the dye transfer process differentiated them and increased the preciousness of the photographs as artistic objects – on the surface his pictures might resemble those of the amateur but because they were printed in this way they were unobtainable to the average person, and therefore elevated to the status of ‘art’.

(Kivlan, 2007) O’Hagan (2017) believes that Eggleston’s accidental discovery led to his instinctual realisation that this would emphasise the singular intensity of “his vision of an everyday America that was both strangely beautiful and trashy.”

Bibliography:

Cocker J. and Holzemer, R. (2009) Imagine: The Colourful Mr. Eggleston. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jZ_HkaTXh8 [accessed 9th January 2018]

Dickinson, A. (2016) Made in Memphis: William Eggleston’s surreal visions of the American South. The Guardian, 8th July 2016. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jul/08/made-in-memphis-william-eggleston [accessed 9th January 2018]

Dyer, G. (2005) The Ongoing Moment. London: Abacus.

Kivlan, A.K., (2015) William Eggleston: Who’s afraid of magenta, yellow and cyan? ASX (Website) Available at: http://www.americansuburbx.com/2015/07/william-eggleston-whos-afraid-of-magenta-yellow-and-cyan.html [accessed 9th January 2018]

O’Hagan, S. (2017) William Eggleston: ‘The music’s here then it’s gone – like a dream.’ The Observer, 19th November 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/nov/19/william-eggleston-interview-i-play-the-piano-musik-photography [accessed 9th January 2018]

O’Hagan, S. (2013) Master of colour William Eggleston wins Outstanding Contribution award. The Guardian, 5th April 2013. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/photography-blog/2013/apr/05/william-eggleston-outstanding-contribution-photography [accessed 9th January 2018]

Szarkowski, J. (1976) Introduction to William Eggleston’s Guide. ASX (Website) Available at: http://www.americansuburbx.com/2010/02/theory-introduction-to-william.html [accessed 9th January 2018]

Szarkowski J. (2002) William Eggleston’s Guide. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Wolmer, B. and Shaw, E. (1976) Color photographs by William Eggleston at the Museum of Modern Art. (Press Release) Available at: https://www.oca-student.com/resource-type/moma1976 [accessed 7th January 2018]

Links: